EIN INTERVIEW MIT AARON PURVIS

von Philippe Blumenthal

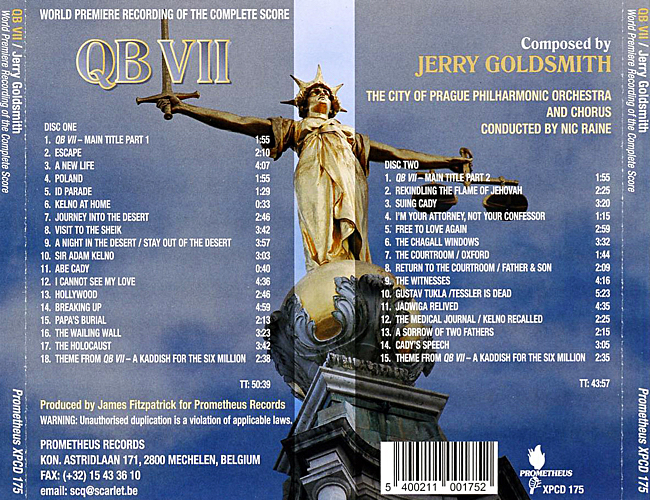

Aufgenommen in Prag mit dem bewährten Orchester unter der Leitung von Nic Raine hat Prometheus in Zusammenarbeit mit Tadlow Music nach Salamander und der Langversion von Hour of the Gun mit QB VII eine weitere „auf anderem Wege“ nicht erhältliche Musik von Jerry Goldsmith herausgebracht. QB VII war eine der allerersten Mini Series fürs Fernsehen – und obwohl die stark gespielte Literaturverfilmung (die für einen Kinofilm als zu komplex erachtet wurde) damals von der Kritik nicht sonderlich begeistert aufgenommen wurde, stellt sie ein Stück Fernsehgeschichte dar. Besetzt mit einem jungen Anthony Hopkins in der Rolle eines polnischen Arztes, der nach seiner Flucht aus dem kommunistischen Polen von Ben Cady aka. Buchautor Leon Uris, Exodus, gespielt von Ben Gazzara, des Mordes und Missbrauchs jüdischer Gefangener in einem Konzentrationslager angeklagt wird, ist QB VII ein eindrückliches Dokument des Grauens des Holocausts. Eine DVD der Miniseries ist nur als Import erhältlich (amazon.co.uk beispielsweise).

Der Score war einer der persönlichen Favoriten von Jerry Goldsmith. Er wurde 1974 von ABC Records (in Deutschland von MCA) und 1995 von Intrada auf CD veröffentlicht. Dies waren bis heute die einzigen Alben von QB VII – und mit knapp 35 Minuten immer irgendwie ein unbefriedigendes musikalisches Erlebnis. Nun haben wir die Möglichkeit auf zwei CDs 94 Minuten Score zu hören, ein weiterer Filmmusikwunsch kann also vom Zettel gestrichen werden. Da von Goldsmiths Musik, die in Rom aufgenommen wurde, keinerlei Notenmaterial mehr vorhanden war, wurde der junge Komponist Aaron Purvis von James Fitzpatrick (Tadlow Music) mit der Rekonstruktion des Scores beauftragt. Wir haben Aaron zu seiner Arbeit an QB VII befragt.

? Aaron, tell us a little bit about yourself please and how you did get to work in film music?

Aaron Purvis: I was born in Los Angeles, raised in Tipton, Indiana. I suppose, in the grand scheme of things, it was rather unlikely that I should be in music at all, never mind be hired to reconstruct the score for QB VII by ear. Ironically, I was born with significant hearing impairment (temporarily deaf), remaining in that condition until I was fourteen months old. My adolescent years were constantly vexed by ear problems and surgery. Fortunately, these issues were eventually corrected.

In spite of that initial setback, I began to use my ears early on to teach myself to play my grandfather’s organ and the piano, mimicking the music I heard on tape, radio, tv, and film. From there, I began to improvise, compose, and write songs. After watching the film-adaptation of Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus, I began seriously to pursue composition on a professional level. This was also my first conscious recognition of the symbiotic relationship between music and film. But it wasn’t until I attended an «Intro to Film Scoring» class with Michael Rendish and Don Wilkins at the Berklee College of Music in Boston, MA, that my interest in working in film became concrete. Since then, I have had the privilege to work with great people from all over the world on short films, documentaries, features, and games.

? What was your reaction when James Fitzpatrick contacted you about the re-recording of QB VII and what is your „personal relationship“ with QB VII?

AP: I am sorry to say that I was not familiar with QB VII at all prior to the commission, and therefore had no personal relationship with it or its subject matter. However, I was naturally very excited at the prospect of working again with such a talented group of professionals. James and I became acquainted through composer Christopher Tin (Civilization IV, Calling All Dawns, etc.). I had worked with Chris on several projects (Hoodwinked Too, Dead Space: Aftermath, Calling All Dawns, etc.), including a documentary called, The Lost Bird Project, which we recorded with James and the Prague Philharmonic. Chris has a long-standing professional relationship with James and had worked with him on several prior re-construction projects. Chris – being the generous soul that he is – suggested that James use me in some similar capacity. I had also been hired to do some orchestrations before by another orchestra in the Czech-Republic (the Hradec Kralove Philharmonic), which may have played a role in getting me the QB VII commission. Truly, I remain grateful both to James and Chris for their confidence in my abilities, and for the proactive manner in which they have encouraged me to use them.

? How well versed are you with the music of Jerry Goldsmith? Did you research some of his other scores regarding the preparing of the re-recording?

? How well versed are you with the music of Jerry Goldsmith? Did you research some of his other scores regarding the preparing of the re-recording?

AP: Goldsmith, along with John Williams, Bernard Herrmann and Danny Elfman, is on my list of top-four favorite film composers. I am therefore very familiar with his music. Growing up in Indiana (the «Hoosier» State), I was greatly impacted by his work in Hoosiers and Rudy, both of which are based in Indiana towns. The inspirational vibe of both of those scores, along with their close connection to my «neck of the woods,» made me feel that even though I come from a small town, I can do anything that is humanly possible, provided I work hard for it and stay positive.

There wasn’t much time between receiving the commission and beginning to work, so I wasn’t able to consult any other Goldsmith scores for reference. However, I do remember watching and studying the score audio for Hoosiers again at the start of the project (I try to watch the film annually!). Even so, I think the score for QB VII is so unique among the Goldsmith repertoire (with the possible exception of the Jadwiga cues) that consulting other scores may have been extraneous anyway.

? How did your work on the re-recording look like (did you make a short score first and then work out the rest?)? I imagine you could get a pretty good idea about the Goldsmith score from the LP/CD release, at least for the tracks featured on that album? But there’s so much more on the new album now…

AP: At the outset, I had scheduled a three-day train-trip across the country, which I decided to use to introduce myself to the project. Fortunately, I had a private room on the train (with a great view of the country-side), which gave me the privacy and quietness I needed to hear and focus on the work. After watching the mini-series all the way through, I sat down with my laptop, a pair of headphones, a pen, and some manuscript paper, and worked out a few of the cues in the middle of the first DVD in their entirety. When I got back to my studio, I began preparing these finished cues in Sibelius (a software for notation). For the rest of the cues, I usually started by mapping out basic tempo-markings and time signatures, and plugging that information into Sibelius. I then worked out the instrumentation, followed by the notation (transcribed by ear, occasionally consulting my piano for confirmation), dynamics, and articulations (these last three usually happened concomitantly). Once all of the cues were orchestrated, I then went back and cleaned up the score and parts, checking my work along the way. As I recall, the whole process took about seven to eight weeks.

AP: At the outset, I had scheduled a three-day train-trip across the country, which I decided to use to introduce myself to the project. Fortunately, I had a private room on the train (with a great view of the country-side), which gave me the privacy and quietness I needed to hear and focus on the work. After watching the mini-series all the way through, I sat down with my laptop, a pair of headphones, a pen, and some manuscript paper, and worked out a few of the cues in the middle of the first DVD in their entirety. When I got back to my studio, I began preparing these finished cues in Sibelius (a software for notation). For the rest of the cues, I usually started by mapping out basic tempo-markings and time signatures, and plugging that information into Sibelius. I then worked out the instrumentation, followed by the notation (transcribed by ear, occasionally consulting my piano for confirmation), dynamics, and articulations (these last three usually happened concomitantly). Once all of the cues were orchestrated, I then went back and cleaned up the score and parts, checking my work along the way. As I recall, the whole process took about seven to eight weeks.

James had given me about a dozen audio tracks from the score, though there was still some slight variation between a few of those tracks and the original on-screen version. The clarity of the audio tracks helped much, but I also had to consult the not-so-clear on-screen version for those cues to make sure there were no variations. The remaining seventy-plus cues (the re-recording combines many of the shorter cues into one track) had to be constructed from the on-screen version only, as there were absolutely no audio recordings or scores for them.

? Having just watched the DVD, I can only congratulate you on your effort. A big advantage must have been how well the music is featured. Most of the time it is pretty good to hear, which isn’t always the case, especially in TV productions. Still it must have been a painstaking effort to listen to the music from the DVD to do score. Not only to detect every single note, but the orchestrations as well…

AP: Thank you kindly. Between the dialogue, the sound effects, and the slight warping of the audio due to the age of the film on which it was originally printed, it proved to be a bit of a challenge to discern the score. On several occasions (particularly when dialogue was present), I had to make an educated guess, as it became impossible to hear what was happening with the music. Fortunately, this score was so intuitive to me – so natural to my background and musical style – that I never felt lost or bereft of confidence. That was really the genius of Goldsmith in this score. It is relatable, natural, and motivational. So, despite the difficulties, I enjoyed every minute I spent on this project.

? Which ones were the most difficult tracks to do and why?

? Which ones were the most difficult tracks to do and why?

AP: I recall there were two tracks in particular that were rather frustrating – for different reasons. Believe it or not, the waltz from «Sir Adam Kelno» caused me such irritation that I had to move that toward the end of my work load (and take a long walk to clear my head for the next cue). The volume levels on the music were so low and the dialogue so high that I really had to strain to perceive what was happening. That was one of the few cues where I had to do some educated guesswork. Listening to it now, it seems so obvious what was happening musically. But back then, in the exhaustion and tension of the moment, it was sort of a puzzle with a few of the pieces missing.

The «Jadwiga Relived» track was very difficult psychologically and emotionally. That scene, which displays the barbarism of the holocaust, is so haunting – the music so dark and ominous – I had to take several breaks to regain my composure. When you watch the scene straight through once, it certainly affects you – but you experience it quickly, fleetingly. But when you spend a couple days with that scene, examining every single second several times over, listening to those screams of torture and instruments of death repeatedly, it really wears you down and weakens you. Fortunately, that was one of the tracks James had sent me, so my reliance on the on-screen version was not as heavy as other cues. Still, I had to scrutinize the on-screen version far too many times. Needless to say, that cue took me much longer to complete than the rest.

? Honestly, after all this work, can you still watch the film?

AP: To be frank, I haven’t watched the film again since completing the project. In large part, I have been too busy to do so. But I’m sure a small part of me still feels a little over-exposed to the film. However, Anthony Hopkins is one of my favorite actors, the subject matter is so poignant and the score has quickly become one of my favorites, so I’m sure it won’t be too long before I find some time to watch the film again!

? Have you been present at the recording?

AP: Unfortunately, I was not present for the recording. I have always wanted to go to Europe, but the opportunities just haven’t been available for that. Plus, there is nothing more satisfying than hearing your work performed, but I was unable to travel to Prague at the time. Actually, I didn’t have a chance to hear anything from the re-recordings until the album was released a few months back (a year and a half later)! So, for the most part, I was on pins and needles the entire time.

? How do you feel about the quality of orchestra’s performance?

AP: I am absolutely elated by their performance. I also feel that Nic Raine, Luc Van de Ven, and Jan Holzner did a tremendous job giving «life» to the album. Before the release, I had come to believe that QB VII is one of Goldsmith’s finest works—a pearl in a sea of diamonds. After hearing the re-recording, I now have an even fonder appreciation for the score, and a very high opinion of the city of Prague Philharmonic Orchestra & Chorus. I count myself as fortunate to have played a small part in bringing this wonderful work back to the fulness of life it deserves.

? What are your future plans?

AP: In the immediate future, I will be completing work with Christopher Tin on his next album, The Drop That Contained The Sea. The album’s premiere will be performed at Carnegie Hall in April, 2014. I’ll also be releasing one of my own concert works for Cello and orchestra, which was recorded by the Prague Philharmonic. I hope to expand upon that work in time, turning it into either a rhapsody or concerto. But the current three-and-a-half minute version will also be available for media licensing. Furthermore, one of my newly self-published works for wind ensemble, El Conquistador, which I wrote over a decade ago, is also ready for distribution, so I’ll be spending some time marketing that as well. Meanwhile, I will continue to seek commissions for composition, orchestration, and/or music editing, both in the U.S. and abroad.

In the remote future, I hope to start making more of a concerted effort producing and publishing many of my songs. Unfortunately, my songwriting career has really been made subordinate to other work, mainly due to opportunity and priorities, so I have about fifty songs (lyrics and music) that still need to be produced and published. I am hoping to be able to balance out my songwriting production with concert works and multimedia projects.

? Thanks a lot Aaron!

Phil, 7.2.2014

Schreib einen Kommentar